COVID-19: Re-evaluating how we produce and how we consume

In light of the current pandemic, there has been a lot of discussion around dietary habits and consumption patterns. This has led me to think about the larger meaning that accompanies our day-to-day food choices. I’m partial to the food I grew up eating – Gujarati food. On my plate, even the simplest rice and rajma seem like an extension of my community, culture and my own childhood. Gujarati cuisine is famously vegetarian, and I have been a vegetarian all my life.

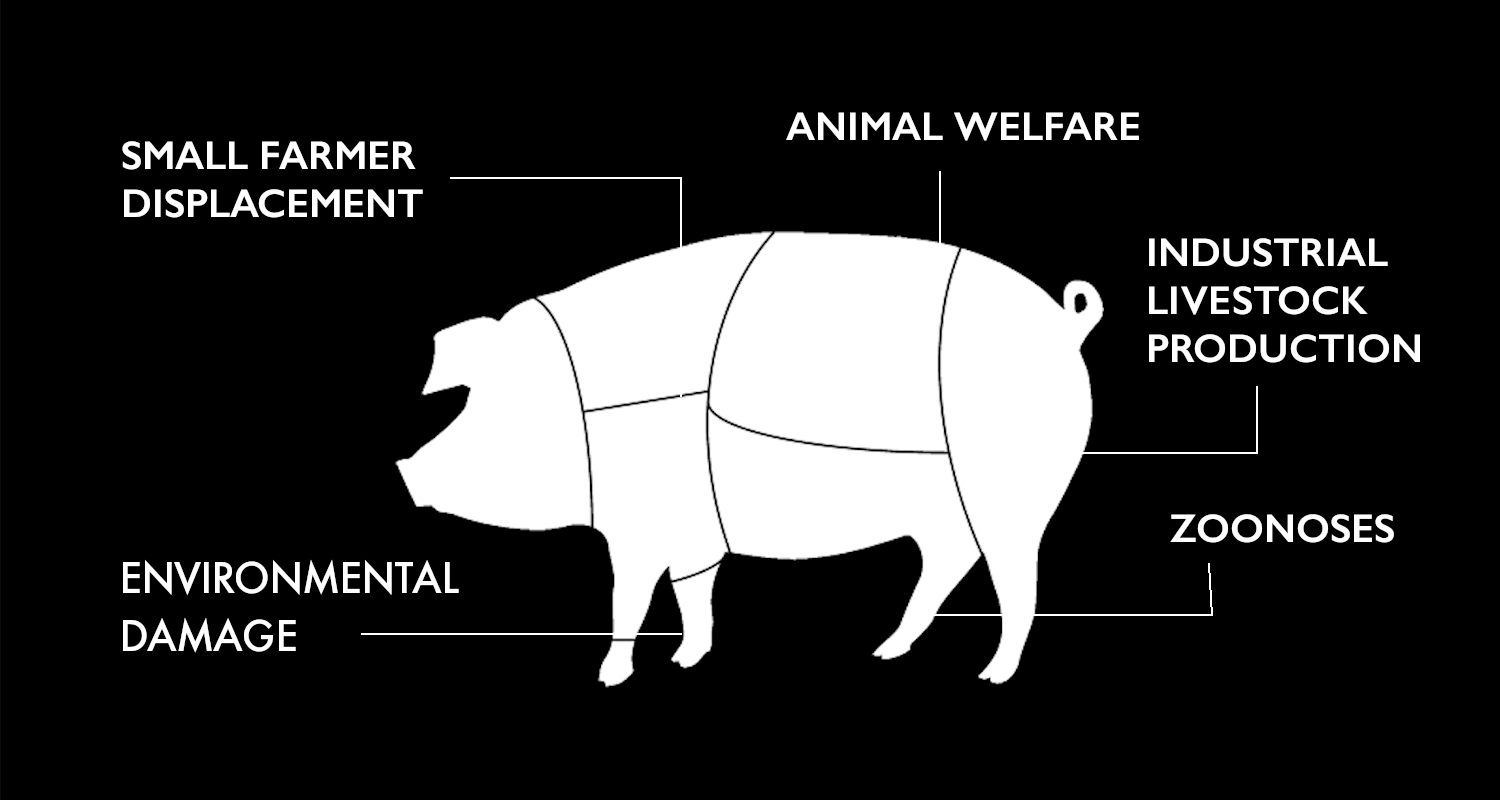

In the context of ongoing debates, I inadvertently find myself on the winning side. There are several well-known arguments for a vegetarian diet. Some people who learn about the factory farming system avoid meat on ethical grounds, because they are concerned about the animals’ welfare. Others who study the effect of the industrialised meat production on farmers and farmland find further reasons to turn vegetarian. Several ground breaking scientific reports have established that refraining from consuming meat and dairy products is the single biggest way to reduce our environmental impact on the planet. It has been estimated that the meat and dairy industries alone, use 83% of farmland globally and generate about a quarter of the world’s greenhouse gases.

And now – there seems to be another reason to take up a majority plant-based diet: our current fear of disease causing pathogens. In a very illuminating article, Laura Spinney of the Guardian traces the origin of a few zoonoses – human infections of animal origin – in modern times. Just the flu transfers from birds to humans account for 15 pandemics that have affected humans during the last 500 years. Spinney quotes spatial epidemiologist Marius Gilbert, of the Université Libre de Bruxelles in Belgium, who says that there is a clear link between intensified meat production factories and the spread of infectious diseases. In other words, it is not just the consumption of meat, but also the manner in which it is produced, that has been the starting point for today’s global crisis.

As I explored further, I discovered that a significant aspect of this process has been the disempowerment of the smallholder farmer in the context of the evolving relationship between humans and our ecological environment.

Spinney's article questions why, given that wet markets in China have been in existence for a long time, the virus is reported to have sprung there at this point in time. Anthropologists Christos Lynteris and Lyle Fearnley have documented the possible side effects of the massive industrialisation of the food sector that has taken place in that region over the past three decades. Smallholder farmers were excluded from livestock farming and compelled to rear animals that were not previously farmed, such as bats and pangolins, which are suspected intermediary carriers of the disease. Many were also driven away from their farms into uncultivable zones at the edges of forests, a move that has affected crop and animal farmers alike. This created several points of contact between humans and wild animals, and their novel, deadly infections. While this is an example from China, similar stories are found in the US and in Europe with respect to the spread of swine flu – some strains of which kill about a third of their human victims. Modern factory farms and intensified agribusiness models, with their density of genetically cloned animals in small spaces, are ripe breeding grounds for zoonoses.

This sentiment has been reiterated in a recent powerful article by Joseph Winters for the Harvard Political Review, in which he describes the gruesome culling of millions of chickens, pigs, and cows by US meat producers, as a result of stalled food supply chains and the ensuring overpopulation of livestock. Besides being ‘a crisis of animal welfare’, it calls into question the structure and system of animal agriculture, and advocates ‘the end of factory farming and the redirection of all government relief and future subsidies towards plant-based agriculture and food processing.’

I have long been a proponent of soya chunks as a viable, vegetarian protein alternative, and it forms a key part of the brand portfolio of Vamara (ETG’s FMCG vertical), packaged as Seba’s Golden Goodness Tasty Soya Pieces. While completely switching to vegetarianism might be too drastic a step for some, even being partly vegetarian would already make a huge difference – as outlined in this inspiring TED video by Graham Hill, who says “After all, if all of us ate half as much meat, half of us would be vegetarians.” Additionally, sourcing meat from independent farmers and certified brands that guarantee animal friendly systems and sustainably produced meat, is another way of responsible consumption.

What we need to be mindful of is that as consumers, we too are accountable for the choices we make. Instead of averting our eyes from the suffering of farmers and their animals now, we should take this time to better understand our relationship with what's on our plate.

Continue Reading

The word ‘CASHEW’ contains the word ‘SHE’

In the regions of Tanzania and Mozambique where ETG has cashew processing plants, 95% of the workforce consists of women. It is the single biggest employer of women in these remote areas.

D4Ag: The Panacea to Africa’s Agricultural Transformation?

The theme of the African Green Revolution Forum 2019 was “Grow Digital: Leveraging digital transformation to drive sustainable food systems in Africa.” This followed the comprehensive “Digitalisation of…

Milestone: Partnering with AGRA at the African Green Revolution Forum in Ghana

It was a landmark moment for me to sign a Letter of Intent with AGRA at the African Green Revolution Forum (AGRF) in Accra, Ghana in early September…

A very good article. I also believe that – What we eat is what we think, and what we think is what we do, and what we do is what becomes our habit, and our habits reflect our character. I also feel that how we treat others (including animals) is the same way the world treats us. So it is important to have a vegetarian diet.